Water Stewardship in Texas

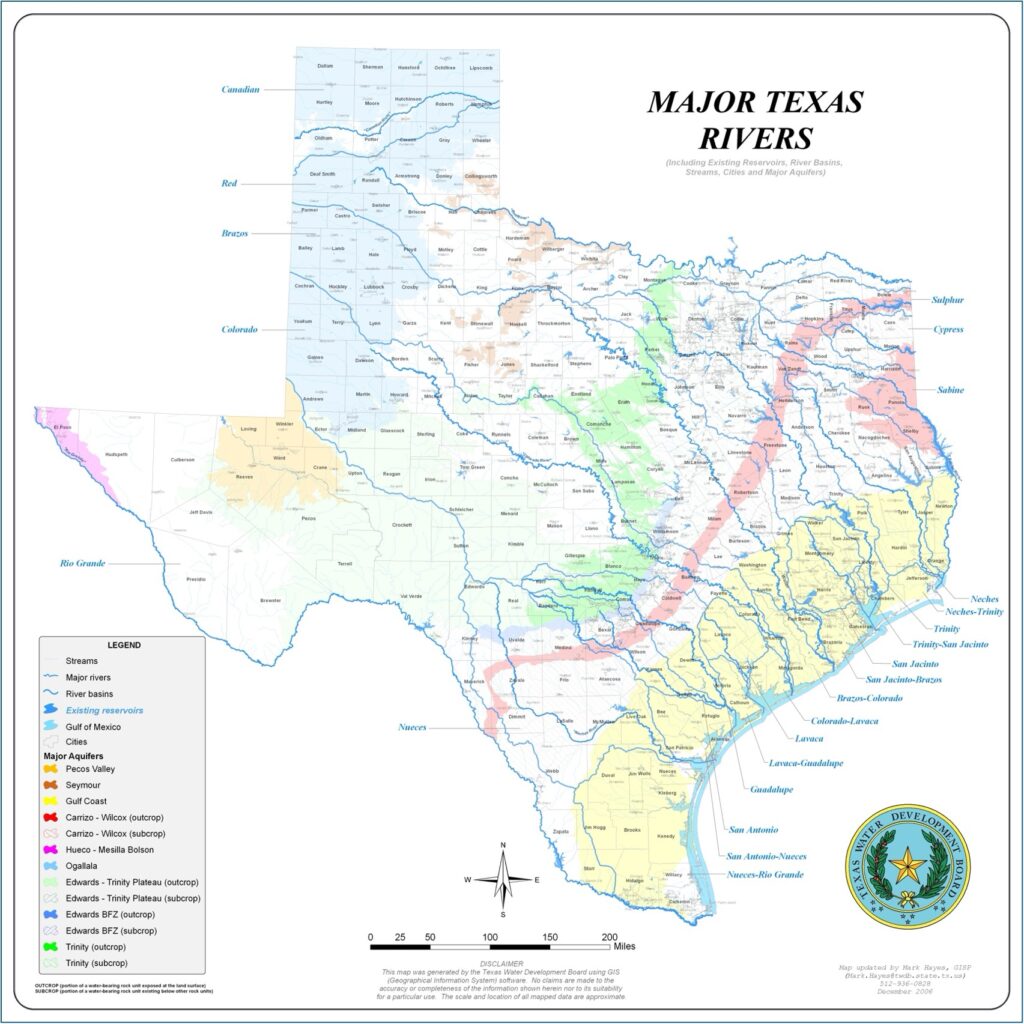

Water stewardship in Texas is a complicated matter and it is made even more perplexing because state water laws do not recognize that surface water and groundwater are connected and interact. As a result the water in our lakes, rivers, and streams are regulated in a very different way than water in the ground. Because groundwater and surface waters interact – the one providing water to the other in many cases – uncertainty arises as water planners attempt to provide adequate water supplies for our future and for the environment. Surface waters effectively belong to the State and are controlled by “water rights”. Groundwater is regulated by the “right of capture” unless a groundwater conservation district has been set up in the location of interest. Where groundwater conservation districts exist, they are the State’s preferred way of managing groundwater resources. Otherwise, Texas has some of the most forward-thinking water laws in the country.

Current trends in water planning leave the Colorado River and counties overlaying the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer at risk. Unless water planning recognize the interaction between the groundwater and surface water resources in Central Texas it is likely that over-pumping of the aquifers will occur and that the impact will not be recognized until it is too late. Current groundwater monitoring of drawdown and well depths do not adequately consider the potential for adverse impacts of dewatering the land and surface waters of the region. Since the aquifers of the region are very slow to recover from over-pumping (taking tens of hundreds of years) serious damage will likely occur before it is recognized and can be corrected resulting in substantial social, economic and ecological damage. Along with rapid growth and development has come pressure on groundwater and surface water resources. Legislative mandates have established water planning and environmental flow projects while population growth has brought demand.

Two major legislative initiatives have driven processes that are helping protect our natural resources while providing for beneficial human uses of water. House Bill 1763 required that groundwater conservation districts (GCD) work together to develop “desired future conditions” for the aquifers under their jurisdiction on a five-year cycle. Senate Bill 3 established the Colorado River and Matagorda Bay Environmental Flows Stakeholder Group in the spring of 2009. The stakeholder group developed instream flow and freshwater inflow standards for the river and bay respectively. Meanwhile regional water planning groups have been established to balance supply and demand.

These planning processes in Central Texas physically intersect in Bastrop County where the Colorado River (the major surface water feature) and the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer (the major groundwater feature) intersect and interact by exchanging water between the two systems, making the river a “gaining” river. Current planning seems to be is leading toward over-pumping of the aquifer and over-disposal of wastewater into the river below Austin, TX.

Over-pumping threatens the groundwater-surface water relationship and could result in the Colorado River losing water to, rather than gaining water from, the aquifer with accompanying damage to the ecology of the region.

Nutrients from wastewater is already impairing river segments 1428 and 1434 between Austin and Smithville. As a result, the “Exceptional Aquatic-Life Use” standard is not being met and the recreational use of the river is in decline.

Though there are numerous government and non-government entities that have interest and/or responsibility for this region, Texas state law treats these issues with such separateness that they are often avoided because they become divisive and contentious and are unresolved at the State level.

Water Planning

Water planning in Texas is currently carried out by three major stakeholder groups. One group is organized along river basins (Regional Water Planning Groups). Another group is organized around major aquifers (Groundwater Management Areas) made up of groundwater conservation districts (GCD). The other is organized along river and bay systems for the purpose of establishing the environmental needs of surface waters (River & Bay Environmental Flows Stakeholder Groups). All recognize political (county) boundaries.

Regional Water Planning Groups (RWPG) representing 16 different regions of the state have drafted plans to meet the water needs of Texas for the next 50 years. The water supply decisions they made will have far-reaching consequences for Texas’ natural environment. As these regional groups and the Texas Water Development Board plan to meet human water needs, they can protect the state’s abundant wildlife resources and cherished landscapes. Poor planning, however, could set the stage for the de-watering of Texas rivers and the collapse of a vibrant coastal ecosystem.

Groundwater Management Area (GMA) The state is currently divided into 16 groundwater management areas. Groundwater conservation districts (GCD) within each management area were required to define ‘desired future conditions’ for the groundwater resources within the GMA. These desired future conditions are a quantifiable management goal such as an aquifer level, a particular level of water quality, a volume of base-flow to rivers, springflow, etc.

Based on the chosen desired future condition, the Texas Water Development Board determines how much groundwater is available (termed ‘managed available groundwater’) for withdrawal. These volumes in turn became the permitting targets for the groundwater districts and are being used in the state’s regional water planning process.

Environmental Flows Stakeholder Groups Water is a vital feature of Texas’ natural heritage. Fish and wildlife depend on water flowing in rivers and streams to sustain riparian vegetation and wetland areas and supply the bays and estuaries along the Gulf Coast with freshwater inflows. More than any other factor, the availability of water will determine the future of fish and wildlife in our state.

Initially, all of the spring flows, stream and river flows in Texas were available as environmental flows. That has changed dramatically as more and more water has been withdrawn for use by humans. Fortunately, nature is adaptable and can tolerate reasonable reductions in flows as a result of human use. The big questions to be answered are how much those flows can be reduced without destroying our natural heritage and how do we make sure adequate flows are maintained.

Environmental Flows

Although the relevant statutes and the Texas Water Development Board’s rules seem to require that the regional water plans include water for environmental flow, the plans continue to fall short. One hurdle is that the overall planning process still fails to recognize environmental flows as a category of water need. Environmental water needs constitute a demand for water that must be met along with municipal, agricultural, and industrial demands.

Two of the planning regions (Region H, which includes Houston, and Region K, which includes Austin and the lower Colorado River area) stand out for having at least recognized the environment as a water need. Unfortunately, not even those groups included measures designed to ensure that water would be left in streams and rivers to meet that need. A couple of other planning groups also acknowledged the need for environmental flows to be more fully addressed. Planning groups also have the option of recommending the designation of unique stream segments. Only a handful of designations were recommended. The Austin-Bastrop-LaGrange segments of the Colorado River should be designated unique stream segments as a result of being designated as “exceptional aquatic-life use”: segments 1428 and 1434.

Unfortunately, the planning groups have had limited time and money to complete the planning process and environmental issues generally have received little attention. Because insufficient attention has been paid to the environmental flows issue, the planning process has failed to develop truly comprehensive plans that address all water needs, including environmental needs. A comprehensive water plan that includes water for environmental needs and also avoids unnecessarily destructive projects is more likely to contain projects that will pass permitting requirements and be implemented than a plan that is prepared without careful consideration of those factors.

Water Conservation

Water conservation is the reduction of the overall demand for water and/or an increase in the efficiency of a water system. Water conservation may be practiced by an individual by curbing his or her personal water use or may be implemented by a water provider by creating programs that improve system efficiency and/or discourage wasteful water use.

Conserving water by consuming less, wasting less, or reusing more reduces costs and postpones or eliminates the need for expensive and environmentally damaging new dams or similar water supply projects. Conservation is superior to new infrastructure development like dams and pipelines as a water management strategy because it is normally economical, environmentally benign and, frankly, wise.